How this fake Norval Morrisseau led to the collapse of Canada’s most brazen art forgery ring

“Spirit Energy of Mother Earth” is the painting that started it all — the fake that brought down a forgery ring profiting off the legacy of one of the towering figures of Indigenous art.

Toronto Star – Nov. 16, 2025

By Betsy Powell, Courts Reporter

BARRIE — Braving the season’s first snowfall, Toronto musician Kevin Hearn made his way up Highway 400 last week for the final chapter in one of Canada’s largest art fraud forgery cases — one that he helped set in motion two decades ago.

“I just keep trying to understand the truth of this matter, as clearly as I can, so I can have some sense of closure,” Hearn said after emerging from the courtroom where a jury heard the final addresses from the prosecution and the defendant, Jeff Cowan.

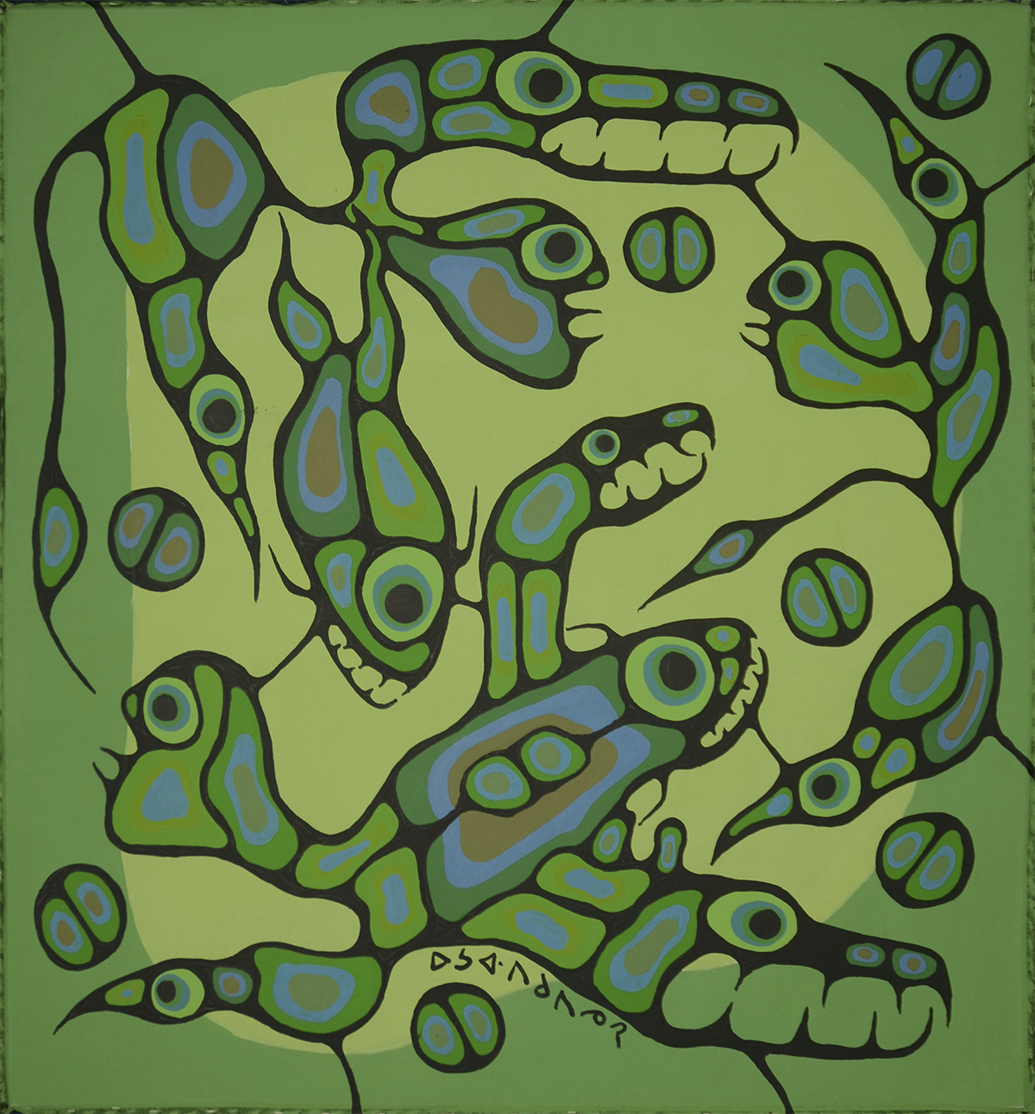

In May 2005, Hearn, best known as the keyboardist for the Barenaked Ladies, bought a painting called “Spirit Energy of Mother Earth,” purported to be by the renowned Indigenous artist Norval Morrisseau. To a layperson, it resembles many Morrisseau artworks — a striking image, with bold figures on a bright green background with the artist’s trademark thick black lines.

But it turned out to be a fake. And there were thousands more.

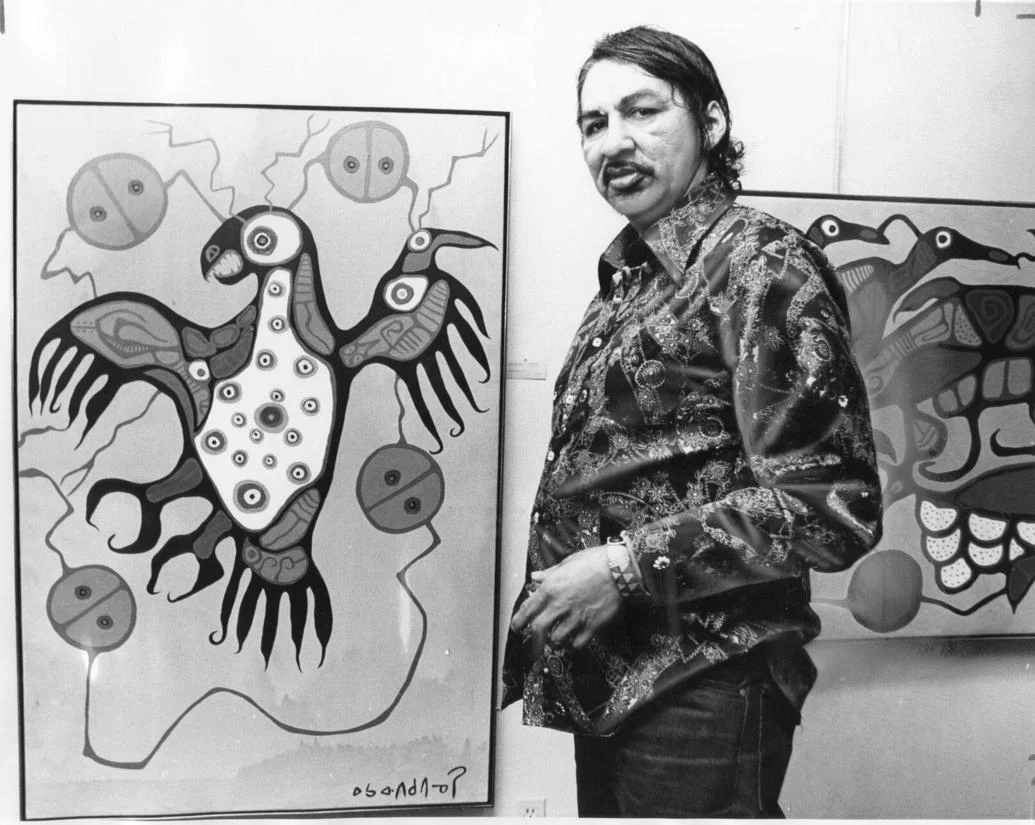

Morrisseau, often referred to as the “Picasso of the North,” remains a towering figure in Indigenous art. Born in 1932 and raised on the shores of Lake Nipigon, he incorporated the traditional knowledge and spiritual training of his grandfather into artworks that became a sensation in the south.

In the 1960s, a Toronto showing turned him into a celebrity and public figure. While Morrisseau, a residential school survivor, struggled with alcohol abuse throughout the ’70s and ’80s, he retained his significance in Canada and internationally — earning numerous awards and honours — until his death in 2007 after suffering from Parkinson’s disease.

Long before his death, there were allegations that forged art was being marketed under his name. Morrisseau himself had complained to the Star that his prolific work was being “ripped off.”

But that’s where it stood until the Art Gallery of Ontario flagged to Hearn that he’d likely bought one of these fakes — “Spirit Energy of Mother Earth” — and he decided to do something about it.

Hearn sued a Toronto gallery and the estate of its late owner, who sold the painting to him for $20,000.

At first, he lost. After a protracted proceeding, the trial judge dismissed his lawsuit, concluding it remained an open question whether the painting was a genuine Morrisseau.

But in 2019, Ontario’s highest court overturned the decision, saying the judge made several errors, including relying on his own research and rejecting an expert who testified it was a fake. The appellate ruling also criticized the trial judge for inserting a Barenaked Ladies reference into his decision.

The legal battle formed the basis of “There Are No Fakes”, a 2019 TVO documentary that prompted a major joint investigation by Thunder Bay police and the Ontario Provincial Police.

Project Totton culminated in the March 2023 arrests of eight people allegedly tied to three interconnected forgery rings that had produced thousands of counterfeit works.

Cowan, a 49-year-old Niagara-on-the-Lake resident who represented himself, is the last of the eight to face justice.

“Fraud on this scale has consequences,” said Lauren Gowler, a Canadian art law researcher at the University of Oxford. “It erodes public trust, distorts our understanding of Morrisseau’s artistic legacy, and inflicts real damage on the Indigenous communities whose stories and symbols were copied, commodified, and sold for profit.”

Norval Morrisseau’s spectacular “Androgyny,” a genuine piece.

Norval Morrisseau’s spectacular “Androgyny,” a genuine piece.

Inside the Norval Morrisseau forgery ring

The first to face justice were Thunder Bay residents David Voss and Gary Lamont, a convicted sex offender. Both eventually pleaded guilty, admitting they oversaw — at different times — the creation and distribution of hundreds of forged Morrisseaus.

Between 1996 and the mid-2010s, Voss forged artworks himself, later establishing an “assembly line” of painters who filled in colours after he drew outlines. These fake works were consigned or sold to distributors and auction houses across Canada.

Kevin Hearn, whose fight to uncover the Morrisseau forgeries formed the basis of “There Are No Fakes.”

Kevin Hearn, whose fight to uncover the Morrisseau forgeries formed the basis of “There Are No Fakes.”

Thousands of forgeries have been identified, though many remain in circulation.

Starting in 2002, Lamont recruited young Indigenous artists to create forged Morrisseaus and operated an online store selling them worldwide.

One of the artists was Morrisseau’s nephew, Benjamin Morrisseau, who later reached a restorative justice resolution with community elders.

Voss and Lamont each received five-year prison sentences.

The sentencing judge said the operation was “more than just an art fraud — it is an appropriation of a cultural and spiritual identity.”

In a victim impact statement, Cory Dingle, executive director of the Morrisseau estate, described the emotional devastation caused by the decades-long scheme.

The wider art world’s involvement

The schemes relied on figures beyond the forgers: Toronto dealer Jim White, appraiser David Bremner, and Jeff Cowan.

White and Bremner pleaded guilty, admitting they authenticated and distributed hundreds of forged artworks — some selling for tens of thousands of dollars.

Only Cowan went to trial.

Bad fakes on Kijiji

Police connected roughly 1,000 forged artworks to Cowan. White testified he bought more than 470 paintings from Cowan, paying over $250,000.

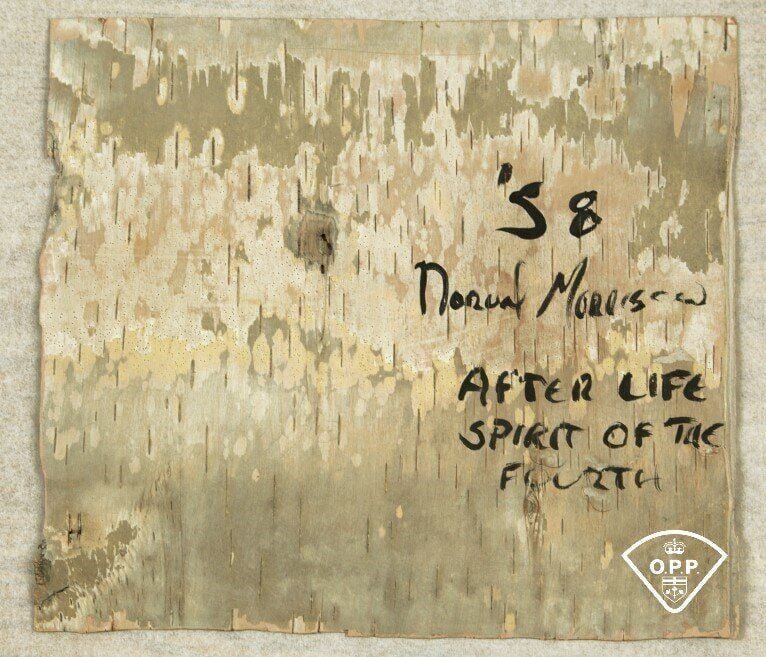

A faked Morrisseau signature, written in English.

A faked Morrisseau signature, written in English.

They weren’t good fakes, the Crown told jurors. Many had signatures in English, even though Morrisseau adopted Cree syllabics in the 1960s — making hundreds of English-signed paintings highly improbable.

Some Cowan-sourced art referenced sexual abuse — something Morrisseau never depicted explicitly.

One forgery was dated 1982 but painted on a pizza box manufactured in 1992 — with a bar code added only in 2006.

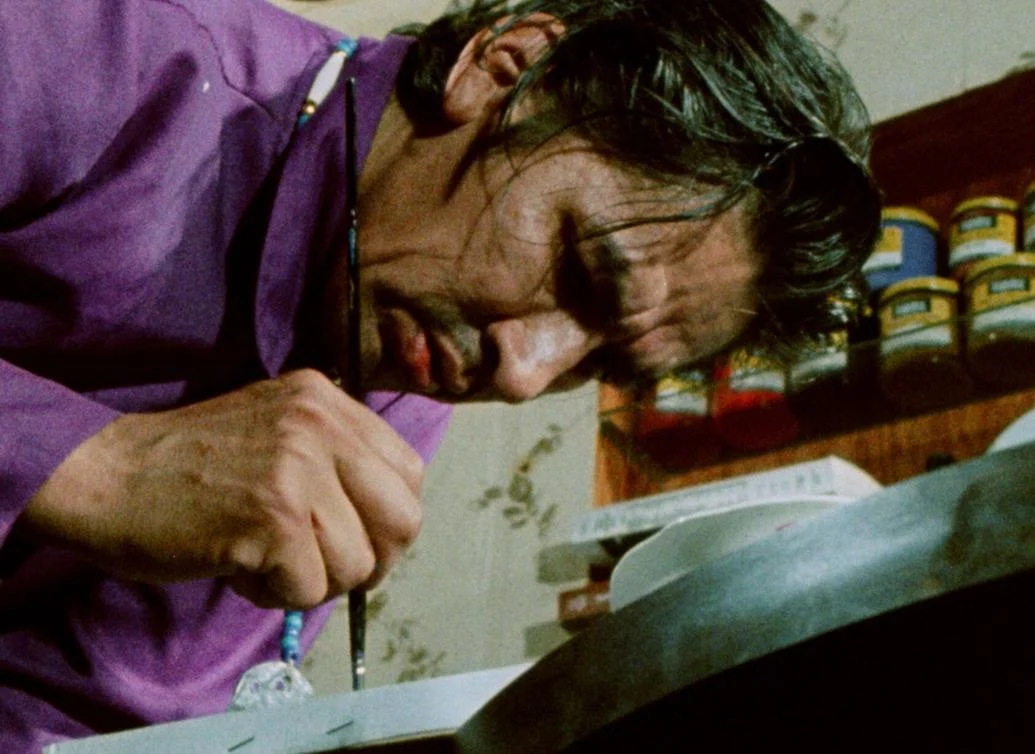

Norval Morrisseau, seen here at work (National Film Board).

Norval Morrisseau, seen here at work (National Film Board).

The final chapter

During closing remarks, Cowan insisted the Crown had not proven the works were fake and accused witnesses of unreliability.

Outside the courtroom, Cowan approached Hearn, telling him he was a longtime fan — an odd moment, Hearn reflected.

Hearn’s painting was traced to Voss, who had supplied White — not Cowan — showing how interconnected the networks were.

After about a day of deliberations, the jury found Cowan guilty of dealing forged documents, defrauding the public, and defrauding two art buyers.

He remains on bail and will be sentenced next year.

According to Gowler, Cowan’s conviction is “an important moment of accountability,” but “the harder work — tracing undetected forgeries, rebuilding market trust, and addressing cultural harm — is far from over.”